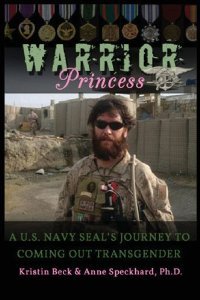

There are many stories now about brave transgender people. This story, though, confronts so many challenging and interesting issues that it is worth a close examination.

At a time in which Chelsea Manning's coming out prompted discussions of whether she has the right to corrective medical treatment while incarcerated, there are broader issues with human rights violations of LGBT prisoners, the criminalization and incarceration of LGBT people, and even broader issues with the general concept of human rights being afforded to all human beings (even those accused of or guilty of a crime). If you are not sure what we mean when we suggest that human rights are not applying to people who are considered criminals, listen to some of the After Innocence stories, and think about the debates over the use of torture in the war on terror, or take a look at HRW's prisons work.

So, the Warrior Princess story is timely and brings out all these interesting questions about patriotism, human rights, soldiers and their personal rights/personal identities.... as well as the broader questions about LGBT people and human rights..... and also broader questions about human rights and freedom of expression, dissent, incarceration, imprisonment, assumptions of guilt/innocence.

On top of that, this topic can help us confront in depth issues of gender, power, authenticity, masculinity, and more. For an introduction to basic terms and concepts that will help, check out Trans101. And read up on Fausto-Sterling.

Thursday, September 5, 2013

Tuesday, August 6, 2013

Not About One Thing: Americanah

Americanah is the new novel written by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie. This award winning author wrote Half of a Yellow Sun. Our book club read that book way back in 2007.

While "Yellow Sun" was situated in Nigeria, this book brings us from Nigeria to the United States, and to the United Kingdom, and back. Through the complicated, interwoven lives we follow in this novel, we encounter multiple, interwoven themes. If they are presented well, human rights issues are complicated, and so are good novels! Just like issues of human rights and women's rights, Americanah is not about "one thing": as Laura Pearson noted in her review, the main character (Ifemelu) in the novel points this out for us in a specific scene in the book. While she is in a beauty salon getting her hair done, Ifemelu is irritated by an attempt at conversation: someone asks her what the novel she was reading was about (groan, it's a novel... it's about a lot of things, how can I possible summarize it for you... is the feeling). Americanah, Pearson notes, is too complicated to summarize, just like Ifemelu's novel: it "covers race, identity, relationships, community, politics, privilege, language, hair, ethnocentrism, migration, intimacy, estrangement, blogging, books and Barack Obama". But it is exciting and challenging to read (a good thing, really!).

So if women's rights are about many things (as well as complicated and interwoven), where are they in this book? Here are a few:

While "Yellow Sun" was situated in Nigeria, this book brings us from Nigeria to the United States, and to the United Kingdom, and back. Through the complicated, interwoven lives we follow in this novel, we encounter multiple, interwoven themes. If they are presented well, human rights issues are complicated, and so are good novels! Just like issues of human rights and women's rights, Americanah is not about "one thing": as Laura Pearson noted in her review, the main character (Ifemelu) in the novel points this out for us in a specific scene in the book. While she is in a beauty salon getting her hair done, Ifemelu is irritated by an attempt at conversation: someone asks her what the novel she was reading was about (groan, it's a novel... it's about a lot of things, how can I possible summarize it for you... is the feeling). Americanah, Pearson notes, is too complicated to summarize, just like Ifemelu's novel: it "covers race, identity, relationships, community, politics, privilege, language, hair, ethnocentrism, migration, intimacy, estrangement, blogging, books and Barack Obama". But it is exciting and challenging to read (a good thing, really!).

So if women's rights are about many things (as well as complicated and interwoven), where are they in this book? Here are a few:

- The novel alludes to the military dictatorships in Nigeria's past, and we encounter the ripple effects of those politics in Ifemelu's Auntie Uju, and her relationship with 'the General'. Auntie Uju's story uncovers the multiple levels of women's participation in politics, and the ways that coups and political unrest can upend everyday women's lives, partly because (all over the world) women's access to legal and civil protection is lacking. When it comes to marriage, common-law relationships, divorce, inheritance, property rights, vulnerability to violence, standards for sexual behavior, this short story illustrates many complications that women must often negotiate from a place of insecurity. Laws are constantly changing, but protections for women lag behind in general and even when it comes to basic human rights such as freedom from violence, when it comes to mistresses, their applicability are still subject to debate.

- In England, Ifemelu's boyfriend from college in Nigeria confronts the dangers of looking for work as an illegal immigrant, including extortion. Ifemelu has her own dangers to confront in that arena in the United States, where her experience is framed by a moment of sexual exploitation: a familiar and disturbing effect of the insecurity inherent in immigrant populations all over the world (especially but not only for women migrants).

- The divisions of race and class that are so strange to Ifemelu, because she is an outsider (to read or listen to an NPR interview with Adichie in the topic of 'learning to be black in the US'), are brought into relief, and presented with ironic and comedic effect in the fictional blog titles of articles that Ifemelu wrote: "Raceteenth or Various Observations About American Blacks (Those Formerly Known as Negroes) by a Non-American Black."; "Not All Dreadlocked White Guys Are Down."; "Badly Dressed White Middle Managers from Ohio Are Not Always What You Think.";"Understanding America for the Non-American Black: What Do WASPs Aspire To?"; "What Academics Mean by White Privilege, or Yes It Sucks to Be Poor and White but Try Being Poor and Non-White." Although it is not explicit, these observations and the experiences that inspire these observations, are also deeply informed by gender, and specifically by the intersections of gender, race, ethnicity, and class.

Wednesday, June 5, 2013

However Long the Night... the Dawn will Break

This is a story of one woman's sense of homecoming in a country and culture that is a world away from the one she was born in.

It is a story of the power of patience, compassion, respect, and determination.

It is a story about the will of people everywhere to achieve dignity and happiness for themselves and their community.

It is a story of how to teach, and how to learn, and how effective (yet how difficult) it is to do both.

It is evidence of how we are all embedded in powerful networks that shape our lives, and of how we are all capable of (indeed, responsible for) improving the world we live in.

"I have always believed that if you feel you are on a path that can lead to the well-being of people, the methods you use to achieve that goal should be respectful, peaceful, and positive... "

The book we are reading for the summer is an uplifting nonfiction book written by Aimee Molloy about Molly Melching, the founder of Tostan. Tostan is a groundbreaking NGO which has shaped education strategies, and development work in Senegal in remarkable ways.Tostan has been identified as an example of "social entrepreneurship", which is a new catch-word in the philanthropic world (although of course the practice of social entrepreneurship is age-old).

Tostan's work started with Molly Melching's interest in Africa, and specifically in Senegal; and with African language, specifically Wolof, the language that approximately eighty percent of people in Senegal speak.

Molly's work in Senegal began with literacy (still a big problem) and children's education. When she started her work in Senegal, there were no children's books in native languages, only in French. These books were written for French children, not for Senegalese children -- so not only were children being asked to learn to read in their second language instead of their first, these kids were also presented with stories that had nothing to do with their actual lives... but rather, about the Paris metro for example! Not much motivation there!

While working on literacy issues, Molly was confronted with the challenges that Senegalese children faced in even being healthy enough to get a basic education. Many children do not make it past five years of age in Senegal, and for many that do, malnutrition and related conditions along with challenges of rural communities with limited access to services and reliable infrastructure make education an uphill battle. From literacy, Molly expanded her focus to literacy and health education in local languages. (If you are interested in this, check out the work of NGO Room to Read, headquartered in San Francisco but active all over the world in children's literacy, girls' education, libraries and book publishing).

She initially thought she would educate women about early childhood health and development: how to take care of their babies and young children. But she discovered (by asking the women themselves) that women really wanted to learn about their own health, because they felt that they did not know enough to keep themselves healthy and were therefore struggling to care for their children and extended families. This shift to women's health education then moved Molly toward human rights education and leadership skill development as well as project management training.Then, women started learning and sharing these really cool lessons and skills, and the entire community wanted in!

Tostan is known for having a local, community defined, community driven approach.

If you are not sure that you would like to buy the book, you can get a good feel for the book by reading this exerpt. You can also watch Molly tell the story of Tostan as a facilitator of "positive disruption" in video:

The book has received some great publicity, as in a PBS NewsHour interview, Melinda Gates reviewed the book; just this year, Molly Melching was named on of the 150 "Women who Shake the World" by Newsweek and the Daily Beast. She was on KPCC's Crawford Family Forum, recently as well.

The New York Times has a great compilation page on the practice of cutting.

So to complete this post, we will explore some basic terms, concepts and approaches that are key to understanding Tostan's approach and provide some social and cultural background.

Why FGC, not FGM?

FGM (female genital mutilation) is an older--but also common--term used to describe the practice of removing some part of a girl's external genitals. The preferred term is female genital cutting (FGC). the term FGC is more neutral, and descriptive. Depending on the community, the practice is called many things: the 'tradition', or circumcision for example. Most women who practice FGC are not participating in the practice with the intent of mutilation, and many do not experience it that way. Rather, it is done out of love with the intention of making a girl socially acceptable, and even more beautiful. Many women all over the world are willing to undergo dangerous and painful practices for these very goals. Molly describes in the book how powerful the social pull of these practices can be, when she finds out her own daughter felt betrayed by her mother for not cutting her. The Orchid Project has a great FAQ page if you would like to read more.

FGC and Islam

While FGC is often thought to be (and even enforced in the name of) religion, the practice is not mandated by Islamic law, and it is not an Islamic practice. In fact, one of the most successful strategies in helping to change this practice is to find religious leaders who are trusted by their communities and can spread the word that FGC is not mandated by Islam. Human Rights Watch's work in Iraqi Kurdistan is a good example of this, and parallels the work of Tostan in Senegal in this regard. There is some resistance here, however:

Knowledge is not Enough

Many women know that FGC is dangerous. The pain that it can cause to mothers (and fathers) as well as daughters is wrenching. Many attempt to circumvent the practice in order to protect their daughters; they put it off, they lie and say that they have already had it done. Molly Melching illustrates very well in her book, though, that better knowledge about how and why FGC is harmful is not enough. As with any social practice, dialogue and the mobilization of men and women together in the pursuit of their shared interest in human rights and well-being is the best and most hopeful way to change harmful social practices.

Harmful Practices are not evidence of Maliciousness

FGC is practiced everywhere, including in the USA

FGC is a practice that is practiced by many people all across the world. This includes the United States, where there are various advocacy approaches and Europe. More than this, FGC is only one practice in a matrix of harmful and/or body altering social practices based on gender inequality that many cultures maintain. For more scholarly reading on this topic, try Transcultural Bodies, Pretty Modern.

It is a story of the power of patience, compassion, respect, and determination.

It is a story about the will of people everywhere to achieve dignity and happiness for themselves and their community.

It is a story of how to teach, and how to learn, and how effective (yet how difficult) it is to do both.

It is evidence of how we are all embedded in powerful networks that shape our lives, and of how we are all capable of (indeed, responsible for) improving the world we live in.

"I have always believed that if you feel you are on a path that can lead to the well-being of people, the methods you use to achieve that goal should be respectful, peaceful, and positive... "

The book we are reading for the summer is an uplifting nonfiction book written by Aimee Molloy about Molly Melching, the founder of Tostan. Tostan is a groundbreaking NGO which has shaped education strategies, and development work in Senegal in remarkable ways.Tostan has been identified as an example of "social entrepreneurship", which is a new catch-word in the philanthropic world (although of course the practice of social entrepreneurship is age-old).

Tostan's work started with Molly Melching's interest in Africa, and specifically in Senegal; and with African language, specifically Wolof, the language that approximately eighty percent of people in Senegal speak.

Molly's work in Senegal began with literacy (still a big problem) and children's education. When she started her work in Senegal, there were no children's books in native languages, only in French. These books were written for French children, not for Senegalese children -- so not only were children being asked to learn to read in their second language instead of their first, these kids were also presented with stories that had nothing to do with their actual lives... but rather, about the Paris metro for example! Not much motivation there!

While working on literacy issues, Molly was confronted with the challenges that Senegalese children faced in even being healthy enough to get a basic education. Many children do not make it past five years of age in Senegal, and for many that do, malnutrition and related conditions along with challenges of rural communities with limited access to services and reliable infrastructure make education an uphill battle. From literacy, Molly expanded her focus to literacy and health education in local languages. (If you are interested in this, check out the work of NGO Room to Read, headquartered in San Francisco but active all over the world in children's literacy, girls' education, libraries and book publishing).

She initially thought she would educate women about early childhood health and development: how to take care of their babies and young children. But she discovered (by asking the women themselves) that women really wanted to learn about their own health, because they felt that they did not know enough to keep themselves healthy and were therefore struggling to care for their children and extended families. This shift to women's health education then moved Molly toward human rights education and leadership skill development as well as project management training.Then, women started learning and sharing these really cool lessons and skills, and the entire community wanted in!

Tostan is known for having a local, community defined, community driven approach.

If you are not sure that you would like to buy the book, you can get a good feel for the book by reading this exerpt. You can also watch Molly tell the story of Tostan as a facilitator of "positive disruption" in video:

The book has received some great publicity, as in a PBS NewsHour interview, Melinda Gates reviewed the book; just this year, Molly Melching was named on of the 150 "Women who Shake the World" by Newsweek and the Daily Beast. She was on KPCC's Crawford Family Forum, recently as well.

The New York Times has a great compilation page on the practice of cutting.

So to complete this post, we will explore some basic terms, concepts and approaches that are key to understanding Tostan's approach and provide some social and cultural background.

Why FGC, not FGM?

FGM (female genital mutilation) is an older--but also common--term used to describe the practice of removing some part of a girl's external genitals. The preferred term is female genital cutting (FGC). the term FGC is more neutral, and descriptive. Depending on the community, the practice is called many things: the 'tradition', or circumcision for example. Most women who practice FGC are not participating in the practice with the intent of mutilation, and many do not experience it that way. Rather, it is done out of love with the intention of making a girl socially acceptable, and even more beautiful. Many women all over the world are willing to undergo dangerous and painful practices for these very goals. Molly describes in the book how powerful the social pull of these practices can be, when she finds out her own daughter felt betrayed by her mother for not cutting her. The Orchid Project has a great FAQ page if you would like to read more.

FGC and Islam

While FGC is often thought to be (and even enforced in the name of) religion, the practice is not mandated by Islamic law, and it is not an Islamic practice. In fact, one of the most successful strategies in helping to change this practice is to find religious leaders who are trusted by their communities and can spread the word that FGC is not mandated by Islam. Human Rights Watch's work in Iraqi Kurdistan is a good example of this, and parallels the work of Tostan in Senegal in this regard. There is some resistance here, however:

Knowledge is not Enough

Many women know that FGC is dangerous. The pain that it can cause to mothers (and fathers) as well as daughters is wrenching. Many attempt to circumvent the practice in order to protect their daughters; they put it off, they lie and say that they have already had it done. Molly Melching illustrates very well in her book, though, that better knowledge about how and why FGC is harmful is not enough. As with any social practice, dialogue and the mobilization of men and women together in the pursuit of their shared interest in human rights and well-being is the best and most hopeful way to change harmful social practices.

Harmful Practices are not evidence of Maliciousness

FGC is practiced everywhere, including in the USA

FGC is a practice that is practiced by many people all across the world. This includes the United States, where there are various advocacy approaches and Europe. More than this, FGC is only one practice in a matrix of harmful and/or body altering social practices based on gender inequality that many cultures maintain. For more scholarly reading on this topic, try Transcultural Bodies, Pretty Modern.

Tuesday, April 2, 2013

A Woman in the Crossfire: Diaries of the Syrian Revolution

From peaceful protests to civil war, the conflict in Syria has been in the news and on the agendas of diplomats since the protests began in March of 2011.

In the recent past, Syria was a stable authoritarian state, with a long history of quiet repression of citizens and incredibly rich heritage, but not a country familiar with violence or chaos in the streets.

At this point in the conflict, Syria is turning into a world-class humanitarian crisis, with refugees crossing the borders into neighboring countries- particularly Turkey and Lebanon.

For a quick overview of the main actors and issues, see this summary by the CBC.It covers Bashar al-Assad and the Assad family, the opposition and FSA, key governments such as the USA, Russia, Iraq and Turkey, and key international organizations such as the United Nations.

The book we are reading is from time in the conflict when it turned increasingly violent. Yazbek, a well known novelist in Syria, and a member of the Alawite minority in Syria, was already something of a rebellious woman at the time of the uprisings. She was divorced, and a professional woman who had made a life for herself and her daughter. While she bravely resisted the regime's atempts to control and then silence her voice, and she finally escaped Syria with her life, she did not escape unscathed, and her experience of the rising tide of repression, rebellion, and violence is shaped by the fact that she is a woman, a mother, a daughter. It is not a pretty story and it is not in a gentle voice that we hear her story, but it is a perspective and a voice that we need to hear in order to really understand the images we see in the news, the numbers we see reported, the political wrangling we hear.

In the recent past, Syria was a stable authoritarian state, with a long history of quiet repression of citizens and incredibly rich heritage, but not a country familiar with violence or chaos in the streets.

At this point in the conflict, Syria is turning into a world-class humanitarian crisis, with refugees crossing the borders into neighboring countries- particularly Turkey and Lebanon.

For a quick overview of the main actors and issues, see this summary by the CBC.It covers Bashar al-Assad and the Assad family, the opposition and FSA, key governments such as the USA, Russia, Iraq and Turkey, and key international organizations such as the United Nations.

The book we are reading is from time in the conflict when it turned increasingly violent. Yazbek, a well known novelist in Syria, and a member of the Alawite minority in Syria, was already something of a rebellious woman at the time of the uprisings. She was divorced, and a professional woman who had made a life for herself and her daughter. While she bravely resisted the regime's atempts to control and then silence her voice, and she finally escaped Syria with her life, she did not escape unscathed, and her experience of the rising tide of repression, rebellion, and violence is shaped by the fact that she is a woman, a mother, a daughter. It is not a pretty story and it is not in a gentle voice that we hear her story, but it is a perspective and a voice that we need to hear in order to really understand the images we see in the news, the numbers we see reported, the political wrangling we hear.

Monday, March 11, 2013

Mali, Peace Corps, Friendship

Mali is a landlocked country, with very low human development (see graph) and gender equity indicators (bottom twenty). If you want a tangible illustration, look at literacy rates (Male: 27%; Female: 12%, report from the NYT)

But as important as these indicators are, they do not tell the whole story.

The history of Mali extends far into the rich inheritances of ancient empires, the modern history of Mali is shaped by French colonialism (until 1960), rebellions and military dictatorships, and transition to democracy but in the context of domestic insurgency and repression (the Tuareg).

Known for their music, the Tuareg are a key element of the politics of Mali and the region. The most recent military coup was fed by arms that came into the country from the 2011 Libyan civil war (something that Human Rights Watch warned about), and in support of separatist Tuareg groups. Saharan al-Qaeda factions took this opportunity to take over the Tuareg area of Mali, however (and there seems to have been some level of cooperation between some Tuareg and some Islamic al-Qaeda style groups). At the same time, in a kind of cultural diplomacy, the rock band Tinariwen has been on a world tour, winning a Grammy and notice from global media. The band directly confronts the tensions and costs of both violent and non-violent rebellion: a few members of the band have been stuck in refugee camps, unable to join in the band's most recent tour. Women as symbol of a people and as active participants in their struggles are clear in some of the band's songs.

In the news recently, Mali has been at center of the now familiar global concern with Islamic militants and terrorism. There is a great interactive backgrounder by the Guardian. The French have stepped in, but want to hand off the responsibility of the intervention to a UN entity soon. In this high-politics context, the issues of women's health and everyday life are often submerged. The closest we may get is perhaps the argument that political stability, governmental accountability and economic development are the only core issues that could resolve conflicts like the one in Mali. Feminist scholars have long argued that this is a mistake.

In the news recently, Mali has been at center of the now familiar global concern with Islamic militants and terrorism. There is a great interactive backgrounder by the Guardian. The French have stepped in, but want to hand off the responsibility of the intervention to a UN entity soon. In this high-politics context, the issues of women's health and everyday life are often submerged. The closest we may get is perhaps the argument that political stability, governmental accountability and economic development are the only core issues that could resolve conflicts like the one in Mali. Feminist scholars have long argued that this is a mistake.

This is why we decided to read this book- perhaps on the surface an odd choice for a group that wants to get some background on a country that is in the middle of an international intervention and coup. But this story is a story of another version of interaction (also with problems and challenges). It is the story of the friendship between a young Peace Corps volunteer and a local woman who is the midwife as well as the only trained source of infant medical care for the town. Monique and the Mango Rains is a story of the strength and resourcefulness of one Malian woman, and the story of the work that she did with very little support. Many Malian women are actively working for change, and it seems important to keep this in mind in the midst of the talk of insurgencies, military force, and negotiations: women can and do have a stake in these issues at all levels.

Another woman who has spoken out in Mali is the artist Moussoulou; I leave you with a sampling of her music (thanks to Patricia, for curating all of the Malian music in this post).

But as important as these indicators are, they do not tell the whole story.

The history of Mali extends far into the rich inheritances of ancient empires, the modern history of Mali is shaped by French colonialism (until 1960), rebellions and military dictatorships, and transition to democracy but in the context of domestic insurgency and repression (the Tuareg).

Known for their music, the Tuareg are a key element of the politics of Mali and the region. The most recent military coup was fed by arms that came into the country from the 2011 Libyan civil war (something that Human Rights Watch warned about), and in support of separatist Tuareg groups. Saharan al-Qaeda factions took this opportunity to take over the Tuareg area of Mali, however (and there seems to have been some level of cooperation between some Tuareg and some Islamic al-Qaeda style groups). At the same time, in a kind of cultural diplomacy, the rock band Tinariwen has been on a world tour, winning a Grammy and notice from global media. The band directly confronts the tensions and costs of both violent and non-violent rebellion: a few members of the band have been stuck in refugee camps, unable to join in the band's most recent tour. Women as symbol of a people and as active participants in their struggles are clear in some of the band's songs.

In the news recently, Mali has been at center of the now familiar global concern with Islamic militants and terrorism. There is a great interactive backgrounder by the Guardian. The French have stepped in, but want to hand off the responsibility of the intervention to a UN entity soon. In this high-politics context, the issues of women's health and everyday life are often submerged. The closest we may get is perhaps the argument that political stability, governmental accountability and economic development are the only core issues that could resolve conflicts like the one in Mali. Feminist scholars have long argued that this is a mistake.

In the news recently, Mali has been at center of the now familiar global concern with Islamic militants and terrorism. There is a great interactive backgrounder by the Guardian. The French have stepped in, but want to hand off the responsibility of the intervention to a UN entity soon. In this high-politics context, the issues of women's health and everyday life are often submerged. The closest we may get is perhaps the argument that political stability, governmental accountability and economic development are the only core issues that could resolve conflicts like the one in Mali. Feminist scholars have long argued that this is a mistake. This is why we decided to read this book- perhaps on the surface an odd choice for a group that wants to get some background on a country that is in the middle of an international intervention and coup. But this story is a story of another version of interaction (also with problems and challenges). It is the story of the friendship between a young Peace Corps volunteer and a local woman who is the midwife as well as the only trained source of infant medical care for the town. Monique and the Mango Rains is a story of the strength and resourcefulness of one Malian woman, and the story of the work that she did with very little support. Many Malian women are actively working for change, and it seems important to keep this in mind in the midst of the talk of insurgencies, military force, and negotiations: women can and do have a stake in these issues at all levels.

Another woman who has spoken out in Mali is the artist Moussoulou; I leave you with a sampling of her music (thanks to Patricia, for curating all of the Malian music in this post).

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)